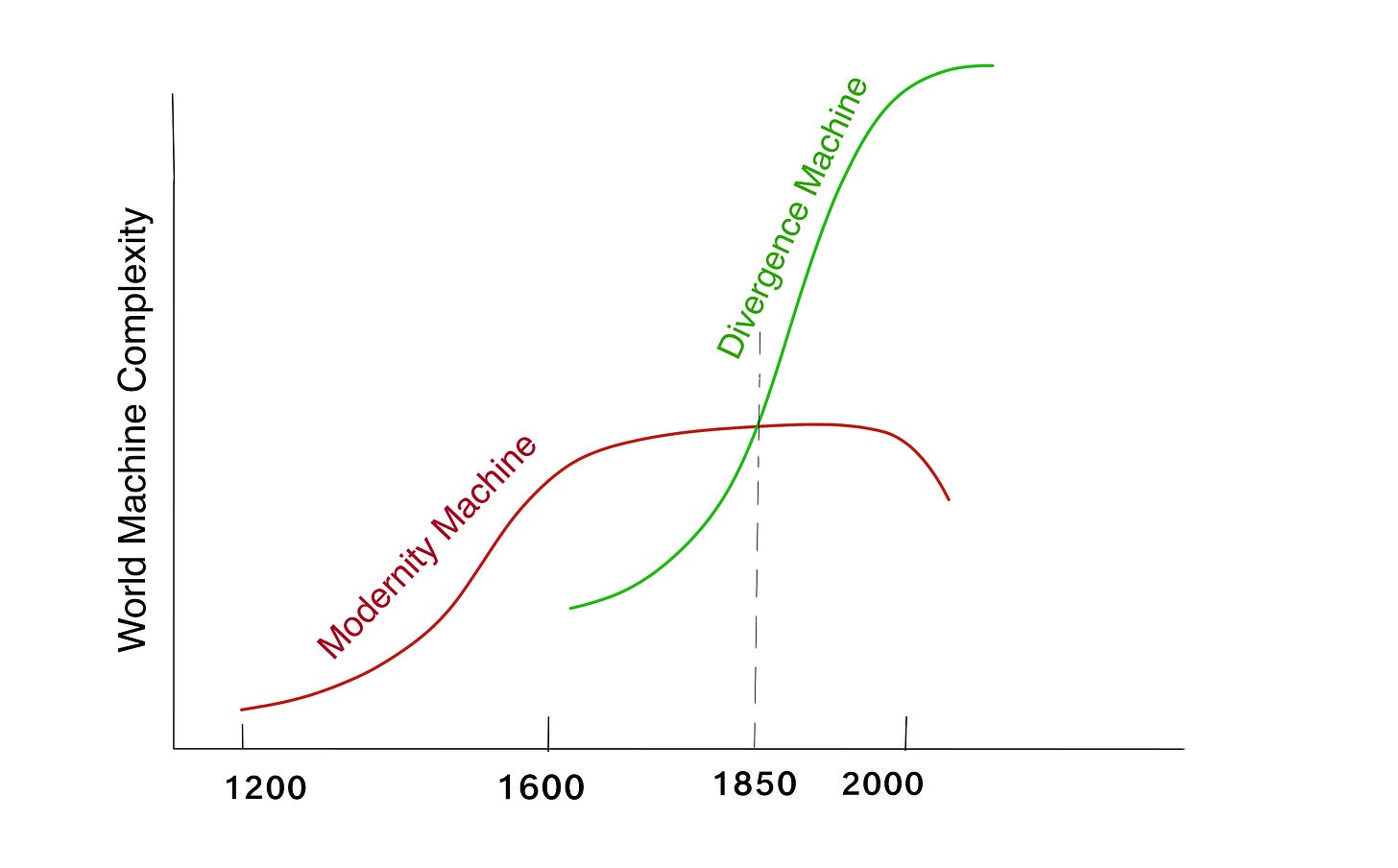

This the third and concluding part of my series with notes on the learnings from the 2025 Contraptions book club. Part I and Part II

traced the construction of the Modernity Machine between roughly 1200

and 1600: a civilization-scale contraption that converted medieval

heterogeneity into legible, interoperable order. By 1600, the machine

was complete in all essential respects. This concluding part addresses

what such completion actually meant, what the machine optimized for once

built, the contradictions it necessarily produced, and why those

contradictions could not be repaired from within.

The aim

is not to declare the “end of modernity,” but to close out a rough

analysis of the machine that took 400 years to build and turn on,

making modernity possible, and sustained it for another 400 years, being

patched in increasingly fragilizing ways along the way. And also to

explore why its very success post-1600 began forcing a slow phase

transition to a different kind of civilizational machinery which began

to get constructed around 1600, right when the Modernity Machine got

turned on. This machine, which I refer to as the Divergence Machine, is

being completed and turned on as we speak, even as the Modernity Machine

is starting to get decommissioned in bits and pieces worldwide. Here is

a teaser picture for the overarching thesis we’re developing here.

The 1600-2000 period and the Divergence Machine that emerged in that period will be the subject of the 2026 book club.

But let’s wrap up 2025 first.

You can catch up on the closing 2025 group discussion in this transcript. What follows is my personal wrap-up.

The

Modernity Machine did not optimize for truth, justice, progress, or

freedom—those were its legitimating narratives. What it optimized for,

relentlessly and across domains, was legibility: the ability to render

people, land, goods, time, belief, and violence enumerable, narratable,

and interoperable at scale.

Venice, in City of Fortune,

is not interesting because it was rich or republican, but because it

functioned as an early, tightly integrated legibility engine: maritime

logistics, double-entry bookkeeping, legal abstraction, diplomacy, and

intelligence-gathering fused into a self-reinforcing apparatus. Venice: A New History fills in the same picture from another angle: stability emerges not from ideology but from procedural compression.

The horse, in Raiders, Rulers, and Traders,

plays a parallel role across Eurasia: a biological technology that

collapses distance, standardizes military force, and forces political

units to scale or perish. The horse is legibility made kinetic.

Printing, in The Printing Revolution in Early Modern Europe,

completes the transition. Knowledge becomes reproducible independent of

context. Interpretation decouples from replication. Information density

explodes while shared meaning lags behind. The machine acquires a

memory that grows faster than any coordinating narrative.

1493

shows the planetary version of the same dynamic. The Columbian exchange

is not merely ecological or economic; it is a global synchronization

event. Previously isolated systems are forced into a single ledger. The

machine’s jurisdiction becomes planetary even as its capacity for

meaning remains local.

Seen this way, the Modernity Machine

is best understood as a civilization-scale compression algorithm. For

several centuries, the gains are extraordinary.

To understand what the machine displaced, it helps to look at relatively pristine end-of-medieval snapshots.

Majapahit

offers such a snapshot outside Europe: a highly developed but still

recognizably medieval empire, organized around courtly ritual, tributary

relations, and localized legitimacy, poised at the cusp of collapse

before modernity arrives in force. It represents a world not yet

reorganized by legibility, still governed by face-to-face sovereignty

and cosmological order.

Within Europe, The Age of Chivalry

performs a similar function. Chivalry appears not as romance but as a

fully articulated medieval coordination system—ethical, military, and

social—already straining under pressures it cannot metabolize. This is

medievalism at its most coherent, just before it becomes an anachronism.

These

snapshots matter because they show what modernity did not inherit:

localized legitimacy, narrative sufficiency, and bounded scale.

Once the Modernity Machine works, it produces three unavoidable byproducts.

First, excess agency. Feudal bonds dissolve, religious monopolies weaken, markets and cities proliferate. The Canterbury Tales and The Decameron

are early catalogs of proliferating voices and moral standpoints.

Social life becomes polyphonic. Coordination becomes harder because more

people can act.

Second, excess information. Printing destabilizes epistemic hierarchy. By Montaigne’s time, the educated individual is already drowning in books. The Complete Essays

read as field notes from the first generation to experience epistemic

overload. Skepticism is both a philosophical stance and a coping

mechanism.

Third, excess scale. Before European Hegemony and When Asia Was the World

make clear that global integration predates European dominance, but

modernity hardens integration into permanent structure. Local meaning

cannot survive planetary circulation intact.

The machine

creates more actors than it can integrate, more information than it can

interpret, and more scale than it can narrate.

The lesson of Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition

is not that Bruno foresaw modern pluralism. It is almost the opposite.

Bruno represents the last exuberant escape of medieval imagination—a

crackpot magician and memory-maven operating within an anachronistic

misunderstanding of Hermeticism as ancient Egyptian wisdom to

hallucinate a worldview of bullshit — indifferent to truth or falsity in

any modern empirical sense. His cosmological conclusions happened to

resonate sympathetically with Copernican implications, but for

fundamentally wrong reasons.

Bruno does not anticipate

modernity; he misunderstands it. His fate marks not the birth of a new

worldview, but the extinguishing of a freewheeling medieval mode

incompatible with both emerging authoritarian modernism, especially

ecclesiastical, and scientific empiricism. What survives of his

tradition—Rosicrucianism, Masonic esotericism—persists as fringe

subculture: culturally influential at times, intellectually irrelevant

to the main currents of modern thought.

Bruno is thus not an early modern prophet, but a terminal medieval outlier.

Similarly, Ibn Khaldun: An Intellectual Biography

should not be read as the story of a proto-sociologist ahead of his

time. That role is largely retrofitted by modern interpreters. In his

own context, Ibn Khaldun appears more plausibly as a kind of depressed

Arab Petrarch: a brilliant chronicler of decline and defender of

tradition, lamenting the absence of an Islamic renaissance rather than

inaugurating one.

His cyclical theory of dynasties does not

launch a new science of society; it records the exhaustion of an old

civilizational form. The importance of Ibn Khaldun here is diagnostic,

not genealogical. He documents a world failing to enter the Modernity

Machine at all, despite being in possession of many of the necessary

components.

By the early modern period, narrative itself begins to fail as a unifying technology. Don Quixote stands as the European bookend to The Age of Chivalry.

Quixote behaves impeccably within a dead symbolic system, and chaos

results. The novel demonstrates that inherited narratives no longer

synchronize action with reality.

Journey to the West

stages the same problem mythically. The Monkey King embodies pure

agency without moral center. Order is restored only through endless

improvisation, not closure. This is not premodern innocence but

recognition that containment now requires perpetual patching, a

condition whose outer story is told in 1493.

Utopia

remains the last sincere architectural drawing of the Modernity

Machine. It assumes total legibility, benevolent coordination, stable

universals, and obedient subjects. Even at publication, it is already

obsolete. The social, informational, and political conditions required

for utopia to function are precisely those modernity has destroyed in

creating itself.

Everything after Utopia

is retrofit to a completed civilizational machine, to patch problems

that began appearing almost immediately after it was turned on in 1600.

By

1600, the machine has crossed a complexity threshold. More law

increases rigidity without legitimacy. More reason fragments into

disciplines. More planning amplifies unintended consequences. More

morality polarizes rather than integrates.

This is not moral

failure or intellectual laziness. It is structural. The Modernity

Machine generates more differentiation than any universal framework can

absorb.

The Modernity Machine does not collapse, but a new

logic begins cohering at its periphery. Coordination shifts from

top-down design to nudging from the margins — and increasingly, everybody

is in the margins. Some just recognize it in 1600, while others are

only realizing it now in 2025. Legitimacy fragments. Meaning localizes.

Systems adapt without consensus. Civilization continues to

function—often remarkably well—while agreeing less and less about what

it is doing or why.

This is the phase transition. The

machine that made convergence possible gives way to a machine that

produces divergence as a default condition.

The Modernity

Machine has done its job. What follows is not its negation, but the

emergence of a Divergence Machine destined to replace it—a different

contraption, hot-swapped piecemeal for its predecessor over 400 years,

between 1600 and 2000. Optimized not for legibility and convergence, but

for proliferation, adaptation, and coexistence without closure. For divergence.

That is the story of 1600–2000, which we will tackle in 2026.

The picks for the first three months have been posted on the book club page if you want to get a head start. I’ll lay out the thesis in a January kickoff post.